Easters in Wola Żółkiewska

– memories

Zbigniew Janisławski (1922-2008) – the son of the owner of Wola Żółkiewska estate told me the story of Easters in his family mansion.

Before we begin, I’d like to say a few words from myself. I had a real pleasure to have contact with people who lived their youth in the Second Polish Republic. Dialogues with them were filled with their living testimony, their current conscientiousness, understanding the sense and the drift of events, their recipes were worth remembering. Even at that time, they were able to notice the importance of daily life. As little kids, they were roaming around the pantry and the kitchen, peeking at icehouses or ovens. They were still clinging to their mothers’ and dinner ladies’ gowns but already watching thoroughly how the adults work. They were asking questions and trying to organize the order of the world in their little heads. Childish games, growing up or youth did not weaken their memory or understanding of the rituals. On the contrary – it strengthened their bond with a larger community and larger circle of contexts and events. Holidays that were celebrated each year as well as husbandry connected works, the same details cherished by their performers were maintaining a tradition and gorgonizing the memory for the hardest times (not as they wished for). The family promise that they will inherit all the world was not fulfilled but what came true was the feeling that they inherited memories. Danuta de Tramecourt, Kazimierz Giza, Zbigniew Janisławski, Franciszek Rzączyński and others… even today, they are not only empty chairs around the Easter table.

Łucja Kondratowicz – Miliszkiewicz

Easter food in Wola was being prepared for the whole week before the celebration. Just like the whole year for weekdays, also during Holy Week, all the instructions related to the preparation of the Easter were given by Mother, Kazimiera née Moskalewska (1878-1931). After her death, our cook Marianna Kaczorowska managed the kitchen.

Everything was prepared then, Easter cake, Mazurek, meat, hams, sausages. The instructions for the servants were the whole ceremony. Mother showed up in the kitchen, always at six in the morning. She set directions – what would be done today for Easter and what would be done for today’s dinner. For all the days of Lent, Mother had a special set of food in her head, so that it would be pious and also so that one wouldn’t starve too much. My father, Ksawery (1863-1940) had his tastes. He always had a beer soup on Friday, which was a traditional, fasting dish. This is actually a breakfast soup, made of beer, yolks, cream, toast or cheese. But the Holy Week before Easter was really putting us all through it. You ate little, on Good Friday almost nothing. There was no relief and the company sometimes simply had enough.

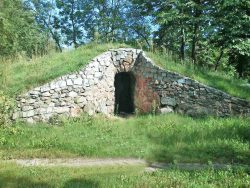

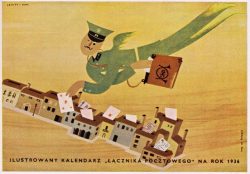

After Mother’s first morning dispositions, Marianna gave detailed instructions. She was the first to go to the estate’s garden and cellars – what vegetables would be needed. Because our cuisine was quite meatless. The second instruction was about the icehouse – how many eggs to bring? What kind of meat? Maria, the daughter of the cook, who was our wardrobe mistress, chose what was needed from the icehouse. Mother chose the meat herself. The third disposition concerned shopping. What else should be bought? Maybe some spices and pepper in a nearby town, Żółkiewka. Or maybe something has to be ordered a little further? I remember that Lithuanian cold meats were brought to the manor house by the “Wołkowysk” mail-order company and even once the “Sienkiewicz” sauerkraut from Vilnius arrived. Everything went by express, they delivered within one day. Those were such times that it was possible to import everything that was needed so quickly. The Polish Post Office issued “Łącznik Pocztowy” [“The Postal Liaison Officer”], there it promoted cheap food parcels, especially to rural manor houses, but also from rural manor houses to families in cities. The parcel reached Krasnystaw by train, then went to Żółkiewka by bus from Krasnystaw to Turobin. Nota bene this private bus company was called “Błyskawica” [“Lightning”].

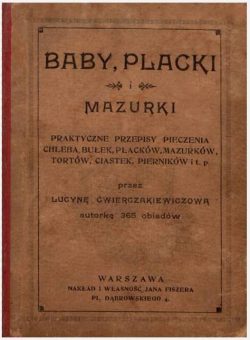

Marianna really lived the kitchen. She had a lot of recipes in her head. We were always wondering how she was doing it all… Because obviously, she doesn’t try what she cooks. She appeared in Wola Żółkiewska when I was a few years old. She came from Belarus, from not so far away from Minsk where she was also a cook at the court. After World War I, there was the first, second and third wave of repatriation. People came back from the depths of Russia after a few years of evacuation or were resettled to the Republic of Poland from the Borderlands, then already Soviet territories. They were being resettled to Poland, and in our country they were being quarantined in three-month camps. One could reach such a camp and hire a repatriate to work. And so dad went to Brest and brought Marianna Kaczorowska and her daughter Maria. Together with Marianna, mistress Ćwierczakiewiczowa herself entered our kitchen, especially my favourite desserts, soufflés and cheese Polish Easter babka.

The kitchen in Wola, as it is in the manors, was big and bright. The room had a Venetian window, a plank floor and walls bleached with lime. There were two ovens, one for cooking with a plate for six stove lids and a large container for heating water. The second one was a bread oven – it held the heat very well because when the hearth was bricked, a layer of broken bottle glass was laid first. Both stoves were heated with wood. The niche between one and the other stove was always stacked with half a cup of wood. All kitchen work was performed on a long table with an oak countertop standing under the window. The second, smaller one, for bread, stood opposite the bread oven. Pots, dishes and instruments were kept in three cupboards standing by the walls.

Baking Polish Easter babka, as you probably know, it was a whole ceremony. In the kitchen it had to be warm, the flour had to be dry, pre-warmed and the yeast fresh. After kneading the dough, Marianna checked if the yeast dough was not too loose. She squeezed the piece in her hand. If the dough is standing, it is good – it is ready to proof! The oven must have been well heated too, but not too hot. Marianna checked the temperature by throwing a handful of flour into the oven. If the flour burned quickly, you still had to wait with the baking, if the flour only blushed, it was a sign that you could start.

In Wola, there were “big” and “small” Easters. As long as Mother was alive, the social life was flourishing and even in summer, about 30 people would sit at the table. When Mother died, life in the manor faded away. So in the 1930s, the guests did not come over that much during Easter, and the table was also more modest.

In Mother’s times, the Easter food was prepared in a large room in the outhouse, then in the dining room in the court. And there the priest was led. I remember that the table at our place was decorated densely with lycophyte and periwinkle. This is what Maria, the cook’s daughter, was doing. In the middle of the table, there was a large lamb, one time made of butter, another time of dough or sugar. We used to place the lamb on the green, usually on the cress. Next to it, there were usually two Easter Polish babka cakes, three-quarters of an elbow high, not glaced, another one babka, but iced and Mazurek cakes. Normally, there should be 12 of them, as many as there were the Apostles. There were several types of Mazurek. One royal, one gypsy, one of dried fruits and nuts with orange zest, and a cheesecake-style Mazurek. This Mazurek was from the east – it was a resurrection. At the beginning of Lent, the extra curd was made from thick cream, it was put into a bag, buried in the ground and dug up for Easter. The royal Mazurek was made of almond dough, with jam on top. The gypsy Mazurek had a lot of raisins, almonds and candied fruit zest. There was also a Mazurek called a “sheet” as it was all covered with white icing. Mazurek cakes were laid on wooden trays made of wooden coasters covered with shark’s tooth paper napkins. In the bowl, there was a ring of sausage, and in this ring there were eggs, and a sprig of periwinkle was stuck. The ham was on a platter, grated horseradish whitened with cream in a bowl, on a plate there was butter and salt in a crystal salt cellar. Once upon a time, but before the war itself quite rarely, there was a baked piglet or a stuffed wild boar’s head with horseradish root in its snout.

Easter basket wasn’t ready without Easter eggs. We did not make a lot of them. A dozen or so to decorate the table. In Wola, Easter eggs were made by Neka, my nanny. She had a special pen and wax. We helped Neka make Easter eggs, and we created the designs spontaneously. The Easter eggs were waxed, topped in three colours. The main colour was onion or light pink from the bark of an apple tree. Other colours were already made from chemical powders, dyeing inks, which were then ready for use, bought.

The liquors were also on the festive table and were also holy. The mansion in Wola is a former defensive mansion, it had three floors of cellars. Liquors were kept on the second level. On wooden shelves stood bottles with tinctures, domestic wines. In 50 l barrel, there was a Starka which is a distilled alcoholic beverage made from fermented rye mash, kept for my wedding, and under the wall, in the sand scattered on the ground, there were bottles with champagne from my father’s wedding in 1898. Dad made tinctures himself. He was known for this hobby. He made walnut-flavoured vodka on green nutshells, milk liqueur, cherry liqueur, sloe gin, plum brandy. He made a lot of wine from white currants. First in glass carboys of 20 l each, then he would pour it into dark bottles, and I would seal these bottles and write with white paint, which year it was. And such wine bottles went to the cellar. As a child, I also had my Easter beverage. Somewhere up to 14 years old, a table with the Easter basket was set up in my room, a special one, for children. In Warsaw, there was a confectionery company Ziółkowski, which specialized in edible toys. They made such sets: marzipan hams, chocolate sausages, chocolate eggs in a bowl, a pig’s head, an Easter Polish babka, and those chocolate bottles with liqueur.

The Easter preparations ended on Friday at three o’clock in the afternoon, because it is the hour of Jesus’ death. On Easter Saturday, first thing in the morning, horses were sent from the manor house to get the priest to bless the food on the table. The priest came, sprinkled the food with water and went back to the church because the parishioners with their Easter baskets were waiting for him there. In Wola, it was not customary for the farm workers or people from the village to come to the manor house with their Easter food. They would ordain their baskets in front of the church in Żółkiewka.

The priest blessed the table and the celebration began. In the past, there were 4 days of celebration, from Easter Saturday to Easter Tuesday. We spent Easter Sunday at home, for the next day we were usually asked to see the priest. Everywhere, to the church too, we walked on foot, also to the Reservation. Because animals need to rest too! And so the horses had a rest!

We started our Easter breakfast by sharing a holy egg, then we had some cold meat, stuffed eggs. It happened once, and I know it from the story, because I wasn’t in the world at the time, that the celebrations could be very modest for Easter in our house. In the morning everyone went to the Reservation, at four, on foot as always. They also came back on foot, they opened the outhouse door and it was empty. The outhouse stood on the edge of the retaining wall. Someone drove up to the wall, sneaked through the window, on ropes they dropped everything that was set on the table. They stole everything, we had nothing, and here it was Easter. Somehow this holiday had to be organized. They asked the neighbours for help, and so one gave some ham, the other gave some of Easter Polish babka, others gave some Mazurek cakes, and somehow they survived Easter with the help of the neighbours and God.

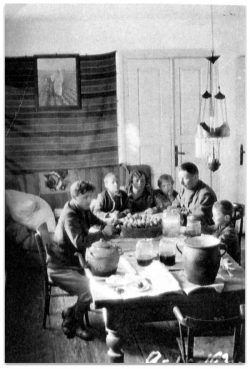

The table with the Easter food in the manor house in Strzyżów, Podkarpackie Voivodeship (photo: NAC, public domain).

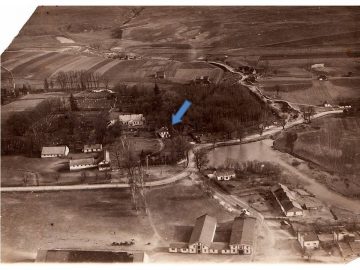

Wola Żółkiewska around 1930, aerial photo by Witold Szyszkowski, aviation lieutenant, husband of Wanda (1906-1969), daughter of Ksawery Janisławski. The outhouse is marked with an arrow, remnant of the former defensive manor from the mid-18th century, reconstruction in 1883, Archive of the Lublin Open Air Village Museum.

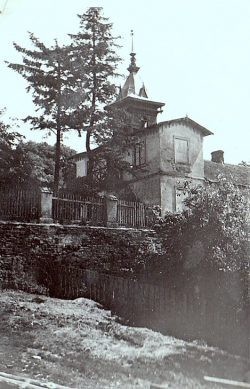

In Mother’s days, Easter food was prepared in a large room in the outhouse, Wola Żółkiewska, photographed about 1930, the outhouse from the courtyard side, Archive of the Lublin Open Air Village Museum.

Icehouse in the estate in Poddębice Grudzińskie, Łódzkie Voivodeship, 2016, source: Album PODDĘBICE https://iwona53.flog.pl.

The 1936 calendar of “Łącznik Pocztowy”, Warsaw 1935.

Metal forms for Easter baked goods, reprod. with: Gechter & Kühne A.G., Heidenau, 3-4 decade of the 20th century…

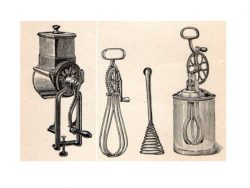

Grinder for grinding almonds, nuts, chocolate and kitchen utensils for whipping the foam, reprod.: M. Ochorowicz-Monatowa, Gospodarstwo kobiece w mieście i na wsi [Women’s Farm in the City and in the Countryside], Warsaw 1914.

Painting of Easter eggs in the Lipiński manor house in Zaturce in Volhynia, Kisielin commune, April 1931, reprod. with: H. Stachyra, Nad Turią i Stochodem, Lublin 2008, after p. 248.

Table with Easter food in an apartment in Łódź, 1937 (photo NAC, public domain).

Table with Easter food in an apartment in Warsaw, 1939 (photo NAC, public domain).

Outhouse in Wola Żółkiewska once again. View of the road leading to farm buildings in the estate – they drove up to the wall, sneaked through the window, on the ropes they dropped everything (the Easter food) that was set on the table.

Kategorie: News | Data dodania: 8 April 2020